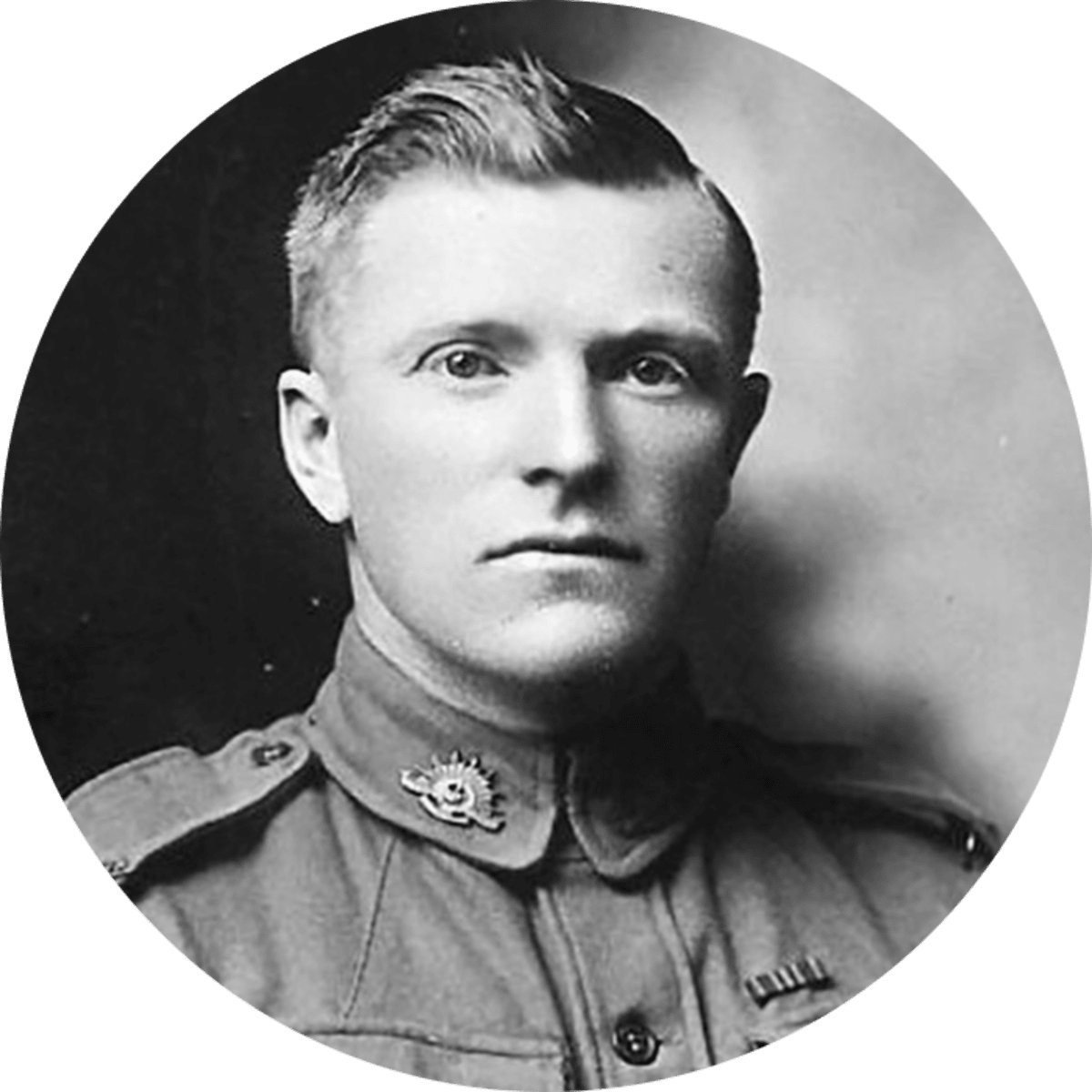

Celebrating the life of

Archie Albert Barwick

In the First World War, Archie Albert BARWICK volunteered to serve overseas with the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). He embarked at Sydney, New South Wales aboard HMAT Afric on 18 October 1914. He was a member of the 1st Infantry Battalion. Archie is remembered by all his descendants for his service and sacrifice. LEST WE FORGET

Join Memories to request access to contribute your cherished photos, videos, and stories to Archie Albert's memory board with others who loved them.

Join Memories